There’s a famous American movie called St Elmo’s Fire, from the 1980s. The plot revolves around a group of kids who had recently graduated from Georgetown University. The plot itself is paper thin, something about them sorta simultaneously being in love with one another and going from self induced crisis to self induced crisis. There’s some other bits, but I guess that’s the relevant part.

Chris Traeger, I mean Rob Lowe, plays a guy who seems to have a problem with hair gel, in that his head seems to feature a lot of it. Demi Moore, pre superstardom, plays a sort of an airhead. Mare Winningham plays Wendy, a sort of shy girl, improbably in love with Chris Traeger. OK, sorry. Rob Lowe. In my opinion, she’s the only halfway likable one. Andrew McCarthy plays a guy brooding over his best friend’s girl, Ally Sheddy. The best friend is played by Judd Nelson, doing his best Patrick Bateman, sans you know, the meat cleaver. I’m not sure what Emilio Esteves is doing in the movie. I guess Gordon Bombay has to graduate from somewhere before he gets sentenced to coach rag-tag group of scrappy pre-teen hockey players. He swoons over his manic pixie dream girl, Andie MacDowell.

It’s one of those movies you don’t watch for the plot. You watch it for the clothes, the handsome young actors and the throbbing, mid 1980s soundtrack. I was 8 years old when this movie came out. I have some small memory of it from it coming out. I was a little more concerned with getting my Hello Kitty pencil cases at that age.

When I moved to DC, I realized that the movie took place in Washington, more precisely Georgetown, a place I had started spending a lot of time in. St. Elmo’s Fire features a lot of wide shots of the area. All brick, green and blue. They ride down M street in a Jeep. It looks beautiful from the outside. They hang out at a bar called St. Elmo’s. Their lives have the hallmarks of post college life. Some of them live in weird pits, others in big apartments, somehow, because movies. Movies. Where babies are born looking like nine month olds and people live in huge apartments, working unpaid internships.

It’s sort of hit me recently that I was these people. I didn’t graduate from Georgetown, but these people had the kind of life that looked glamorous from the outside. I guess my life looked pretty glamorous from the outside too.

Georgetown was a place I spent a lot of time in during those years. I was with this temporary group of friends I had at the time. The son of a cabinet official who seemed deeply unsatisfied with so many aspects of his life. The daughter of a very old American family who life looked so beautiful from the outside. She lived in her family’s house in a posh part of DC, quite posh. The part that I left out was that her family had fallen apart in a really sad and heartbreaking way. Her house was full of pictures of the family together at holidays, impeccably dressed. The sad part was that except for her, everyone was in different corners of the planet, the family broken by an acrimonious divorce.

Growing up the way I did, never sure if we were going to stay in America or go back to Poland, those people looked like they had the perfect life. In my utter naiveté, I thought people like that didn’t have any problems. Seeing the inside of this house, like hundreds of others I had seen from the outside before looked so beautiful from the outside, but the inside was just like mine, filled with the normal ups and downs of life.

Sundry hangers on joined this group of people, my own St. Elmo’s crowd. There was a lot of partying, drinking, so on. I remember so many nights going to Nathan’s bar on Wisconsin and M, I guess our version of St. Elmo’s.

You never believe how glamorous people’s lives look like from the outside and ours certainly did. Our lives looked a lot like the St. Elmo’s crowd. Young, privileged and full of promise. The thing was that even the ones on the inside thought of themselves as being on the outside. I looked like I was on the inside of the crowd but I was on the outside too. To me, even my crowd, I was on the outside. I was sitting on the outside of them where the whole world saw me as a part of this world.

At 46 I realize how much you are still a kid at 26. At 26, I was already so behind everyone else. Everyone was thriving in their careers, their personal life was going from strength to strength and everything was just going along swimmingly for them. Everything had to happen at 26. Once I hit 30, I mean nothing would happen anymore. When I was 26, to me I was alone with my Milano cookies, my cameras and my foreign film DVDs. There were nights out in Georgetown, but there were also lonely nights on Maryland avenue. Little did I know that as quickly as things can come together and work out, it could fall apart and that certainly would happen for this crowd. And sometimes falling apart meant falling into something better.

Sometimes I think about how grownup we all thought we were. We really did think we were adults, with our conversations, but really we were just kids. And if I’m really honest, elites. Part of the one percent. I chafed at this description for a long time but now I can see how I am a part of this class of people. Monetarily, no, I wouldn’t have put us into that 1% tier, but I could take advantage of any educational opportunity I wanted to go after, including the unpaid internship I did when I first got to Washington. Then I did another extremely low paid internship after the first one. None of this was a real problem money wise.

Success came early and from my perspective, too easily, when I first got to Washington. I did my best to fit into this crowd, but the feeling of being an imposter never really wore off. We were all at Nathan’s, our St Elmo’s, pretending to be adults. Us with our big, important jobs thinking we were the kings of the world.

The more I describe this, the more arrogant and self important I sound, but we were part of an extreme elite. A couple of years ago, I taught in a community college in a small community near Boston. I’m not going to go into any noblesse oblige here about the experience. I loved those people. I remember teaching them and thinking how different our experiences coming to America had been. Most of them had left their home countries and come to the United States and worked in factories or as Uber drivers. My dad came as a post doc at a very elite American university. The media tends to paint immigrants as a kind of a monolith. My experience coming here had been so vastly different from theirs. I was at once with these people but also separate from them.

Because of my dad’s brain and a lot of good fortune, I ended up in that crowd in Georgetown, that St Elmo’s life. I never shook the feeling that I really did not belong there. It’s hard to describe how the situation felt like from the inside, from what it looked like on the outside. From the outside, we were these super elites with these fancy jobs and resumes already full of a lot of upper middle class enrichment activities. Study abroad, unpaid internships at great places, studying under incredible experts.

But what it looked like from the inside was vastly different. It felt like this endless pissing contest about who had done what better thing. Who was doing what better thing. And everyone played this contest of “who knows who,” which I absolutely hated.

The pissing contest about what you had already done always went something like this. Me: I studied in Copenhagen and Krakow. I went to Russia, Estonia and Poland while was there. Them: oh, so you didn’t travel while you were there? When I did study abroad in London, I traveled around Europe every weekend. I went to….. this long list of places. Me sort of slinking away, thinking I was a loser because my parents couldn’t give me the money to travel as much as this person had. And also conversation over, quickly. Rinse and repeat. I remember other conversations that involved asking which building that person had worked in during their internship on the hill. To me, it stunk of “I’m letting you know I know the names of buildings on the hill and you cannot stump me.”

The “name the place and I’ll tell you who I know from there” game infuriated me further. I worked at this specialty press in Fall Church with Herman and this eclectic cast of character. Eclectic. I guess that’s the ten dollar word I would use to describe my coworkers at the tax shack. Herman was a high school salutatorian from New Jersey who had studied biochemistry, had known Edward Albee, was an extra in a Keanu Reeves movie, owned a bookstore in Baltimore and was the editor of the product I worked on. I don’t know who he knew, but I knew he was fun to hang out with and my best friend. A lot of those conversations about “who you know, do you know….” revolved around asking a person where they work and then asking if they know this person over there. Somehow Tax Analysts never entered the chat. Not major league enough, not fancy enough I guess. I found this extremely tiresome. One time with Little Edie, we were with one of her colleagues from her much more prestigious work place and he was Australian. Little Edie asked him if he knew some other Australians in DC. I turned to the guy and asked him if he know Elle McPherson and Mel Gibson. The guy chuckled and said — no I don’t. They didn’t go to my high school.

I think in a way, we were fooling ourselves. At 26, your job defines you. It is your entire world. At 46, I realize that what you do for work doesn’t define you. What defines you is the kind of person you are in the world. Are you a generous person? Are you kind? More importantly, are you kind to the people you know cannot do anything for you? Who were we really at that age? Who are we really at 26? Just kids.

Recently, I went to a conference at work about the intersection of sociolinguistics and disability studies. We heard an incredible talk by an anthropologist/linguist about a newly formed language he had studied. At the beginning of the talk, he called us all “weird.” Interesting opener, I guess. But he meant this acronym that is used in psychology research that stands for White Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic. The striking part about that acronym is that it represents just 12% of people on planet earth, but is used as the metric for most psychological research. The St Elmos/Nathan’s crowd, us, we were “w.e.i.r.d”. A small slice of “weird.” The luckiest group of people in the world and yet somehow deeply insecure about our place in the world. But most of all, just kids. We were just kids.

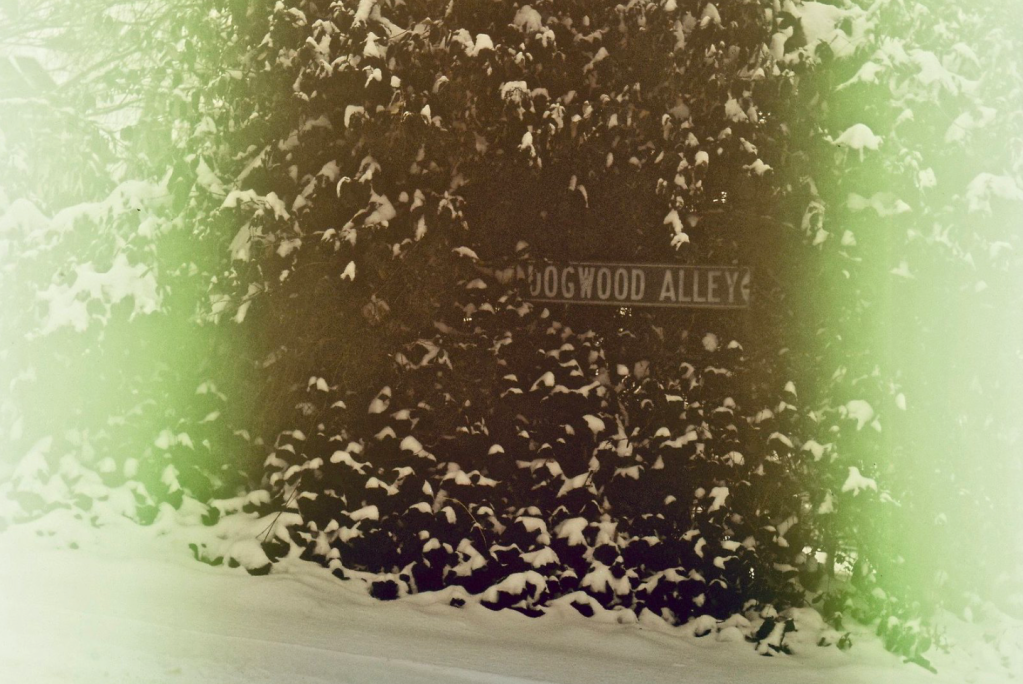

Well congratulations. You made it down this far. Let me reward you with pictures of Georgetown, past and present: